Mainak Banerjee, Bhanu Malhotra, Rimesh Pal

Dear Editor.

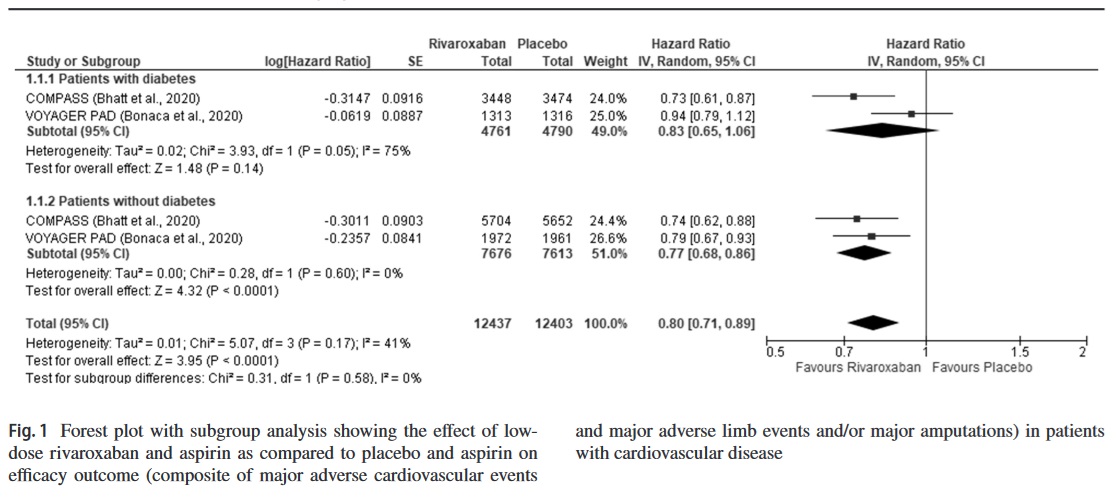

The Cardiovascular Outcomes for People Using Anticoagulation Strategies (COMPASS) trial and the Vascular Outcomes Study of ASA (acetylsalicylic acid) Along with Rivaroxaban in Endovascular or Surgical Limb Revascularization for PAD (peripheral artery disease) (VOYAGER PAD) trial have demonstrated that compared to aspirin alone, low-dose rivaroxaban and aspirin significantly improve major adverse limb events (MALE) and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) or peripheral artery disease (PAD) [1–3].

Diabetes mellitus is a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases (CVD). Previous studies have shown that 20–30% of patients with PAD and nearly 20–50% of patients with CAD have diabetes [4]. As compared to non-diabetic patients, subjects with diabetes tend to have more diffused infrapopliteal arterial disease and poorer outcomes in terms of more amputations and higher mortality. Similarly, CAD patients with diabetes have more severe and diffuse angiographically documented coronary artery involvement compared to non-diabetics [5].

Considering the peculiarities of diabetes-related CVD, it is intriguing whether low-dose rivaroxaban would have similar beneficial effects in such subjects. To address the lacunae in the existing literature, we undertook a systematic review and meta-analysis to collate the effect of low-dose rivaroxaban with aspirin as compared to aspirin alone in patients with cardiovascular disease (CAD or PAD) and diabetes mellitus.

The systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement [6]. Two independent investigators (RP and MB) performed a systematic search of the literature across the PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, and Web of Science databases from inception till October 31, 2022, using the MeSH/Emtree terms and/or appropriate keywords interposed with Boolean operators. The search strategy has been elaborated in the Supplementary Appendix. Only randomized controlled trials looking into the effect of low-dose rivaroxaban with aspirin vs. aspirin alone in patients with cardiovascular disease (CAD or PAD) and diabetes mellitus were considered eligible for selection.

Two investigators (MB and BM) independently scanned titles and/or abstracts to exclude duplicate studies and studies that failed to meet the aforementioned eligibility criteria. Potentially eligible studies were full-text assessed. Any discrepancies between the aforementioned investigators were solved by discussion, consensus, or arbitration by the other investigator (RP). The following data were extracted from the included studies: the study characteristics (first author, year of publication, country), number of patients with diabetes mellitus receiving low-dose rivaroxaban with aspirin vs. aspirin alone, median duration of follow-up, composite efficacy outcome reported in each of the included trials, and primary safety outcome reported in each of the trials. The risk-of-bias assessment was carried out independently by MB and BM using version 2 of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2).

After a scrupulous and meticulous literature search, two randomized controlled trials, namely the COMPASS and the VOYAGER PAD, were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1). The study characteristics have been summarized in Supplementary Table 1. In short, the COMPASS had included patients (n = 18,278) with CAD and/or PAD [3], while the VOYAGER PAD had included only patients (n = 6564) with PAD who had undergone revascularization [2]. The proportion of participants having diabetes at baseline in the COMPASS and VOYAGER PAD was 37.8% and 40.0%, respectively [2, 3]. Both the studies had a low risk of bias.

The hazard ratios (HR) of the efficacy and safety outcome reported in the trials, namely the composite of MALE/MACE and major bleeding, respectively, were pooled together using the generic inverse variance method with fixed-effects/random-effects model. For each pooled analysis, we performed a subgroup analysis between patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Statistical heterogeneity among studies was assessed using I2 statistics. A p value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the RevMan 5.4 software.

Pooled analysis showed that low-dose rivaroxaban and aspirin did not result in a significant improvement in the composite outcome compared to aspirin alone in patients with CVD and diabetes (HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.65–1.06, p = 0.14, I2 = 75%, random-effects model); nevertheless, in patients without diabetes mellitus, the drug resulted in significant benefits (HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.68–0.86, p < 0.001, I2 = 0%, random-effects model) (Fig. 1). Even in patients with diabetes who had undergone revascularization at baseline, rivaroxaban was not found to be beneficial (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.69–1.06, p = 0.15, I2 = 55%, random-effects model) (Supplementary Fig.2).

With regard to the safety outcome, pooled analysis showed that the risk of major bleeding was increased in patients with diabetes mellitus receiving rivaroxaban (HR 1.82, 95% CI 1.38–2.40, p < 0.001, I2 = 0%, random-effects model). On the contrary, in patients with no history of diabetes mellitus at baseline, rivaroxaban did not increase such risk (HR 1.37, 95% CI 0.84–2.25, p = 0.21, I2 = 69%, random-effects model) (Supplementary Fig. 3).

The meta-analysis challenges the notion that low-dose rivaroxaban added to aspirin improves cardiovascular and limb outcomes in all patients with CVD and testifies that it might not offer any additional advantage in diabetes-related CVD. This apparent disparity seems unclear but can be explained based on more severe and diffuse arterial involvement in diabetes-related PAD/CAD than in those without diabetes [5, 7]. Besides, the high prevalence of polypharmacy and co-existing comorbidities seen in CVD patients with diabetes mellitus might also explain the poor prognosis and higher risk of bleeding with rivaroxaban use.

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s13410-024-01373-x.

Author contribution MB is the primary author. BM helped in data extraction and in editing the manuscript. RP is the corresponding author, performed the statistical analysis, and helped in editing the manuscript. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest The authors declare no competing interests